Vi har hytte 585 meter fra husene på gården. Det er Strandstua.

Litt kort vei til hytta, kanskje? Men det er mange ganger veldig greit å kunne ta en miniferie, bare for noen timer. Og til sosiale sammenkomster er det uovertruffent.

Strandstua ligger i fjæresteinene rett under Eidsfjellet, og det er takket være en kombinasjon av direkte råflaks og steinhard jobbing som gjør at vi er stolte eiere av denne perlen av en idyll. Takknemligheten fyller oss hver gang vi trør over dørstokken.

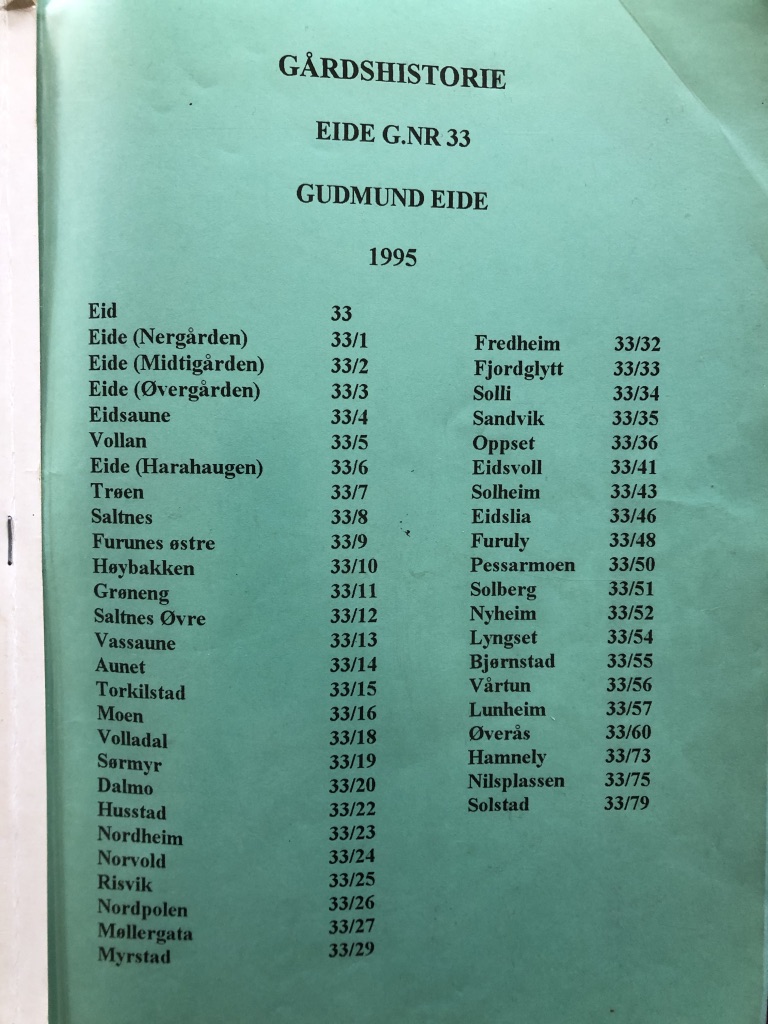

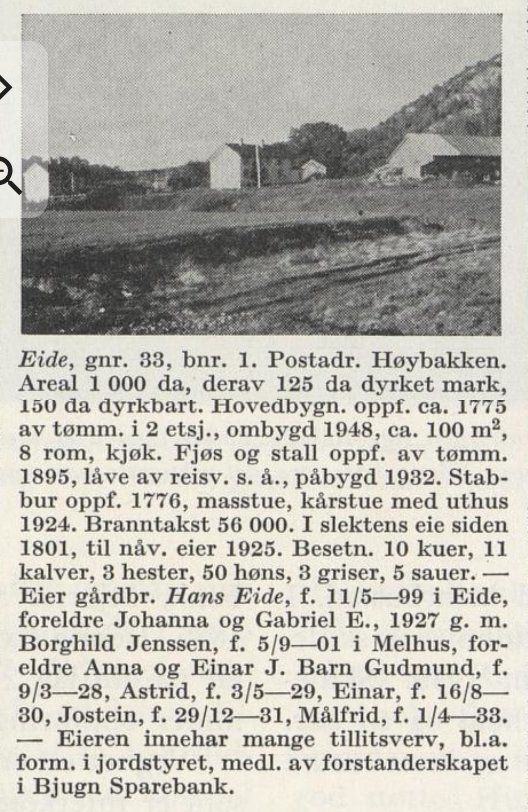

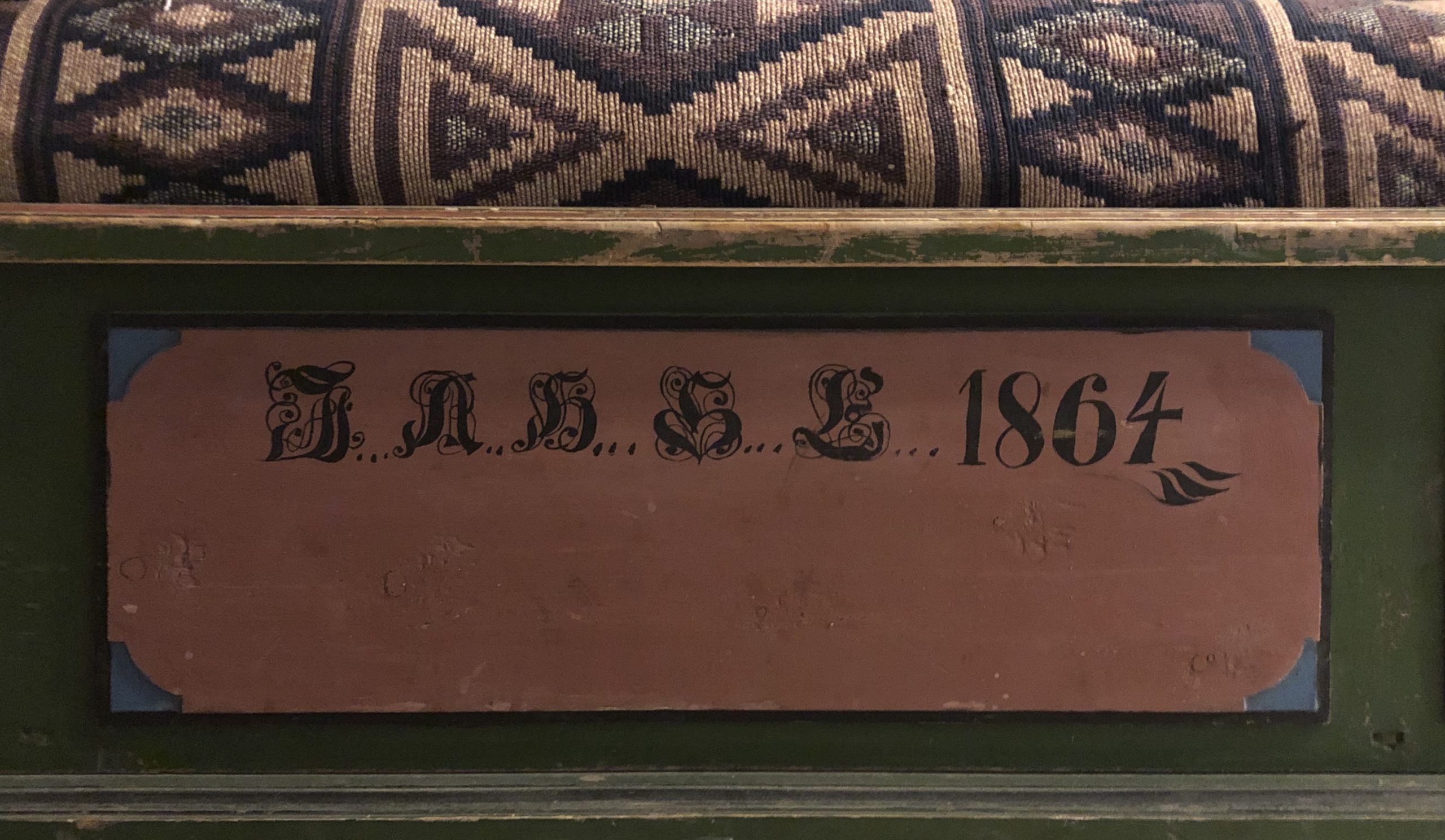

Historien til Strandstua starter i 1941, når Edvin Risvik kjøper en liten flekk land av Hans Eide (bestefar av nåværende eier), helt nede ved sjøen, antakelig en gammel strandsitterplass. Her setter han seg opp ei lita stue året etter, i 1942. Men det er krig, det finnes lite og ingenting å få skaffet av byggematerialer, grunnmuren blir nesten bare sand og stein, med en liten tanke sement hist og her.

På loftet er det ett lag med planker til vegg — en kan se tvers gjennom veggen mellom sprekkene. Men det er uansett bare på sommeren de bruker loftet.

Edvin er fisker, og sammen med sin kone Anna eier han en liten motorisert fiskebåt med kahytt. Når det blir for kaldt og for lite ved til å holde varmen i huset, ligger de i kahytten om natta. På fjorden blir det aldri så kaldt som på land, og det trengs langt mindre ved for å holde den lille kahytten varm.

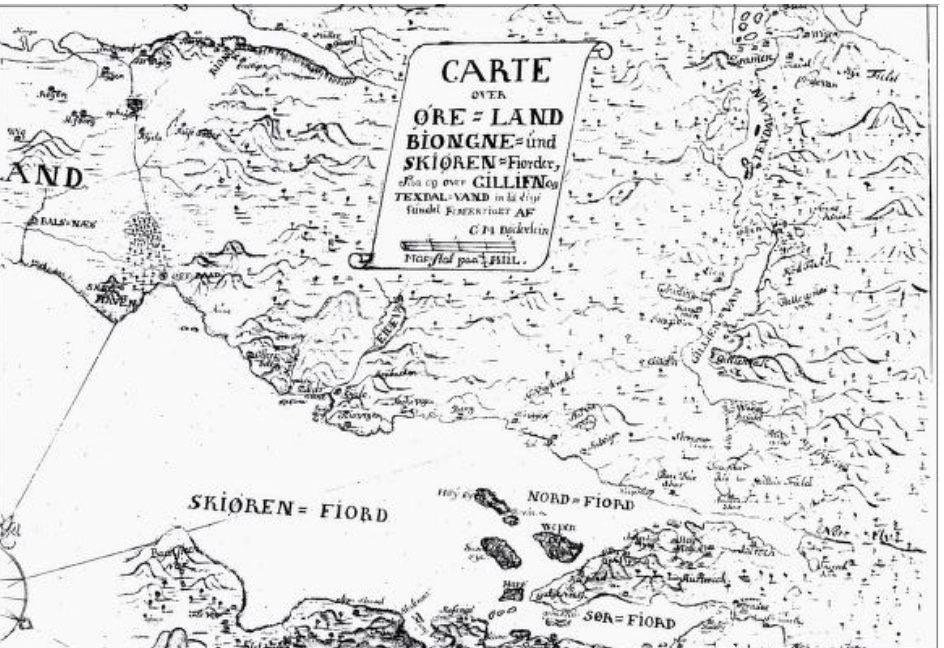

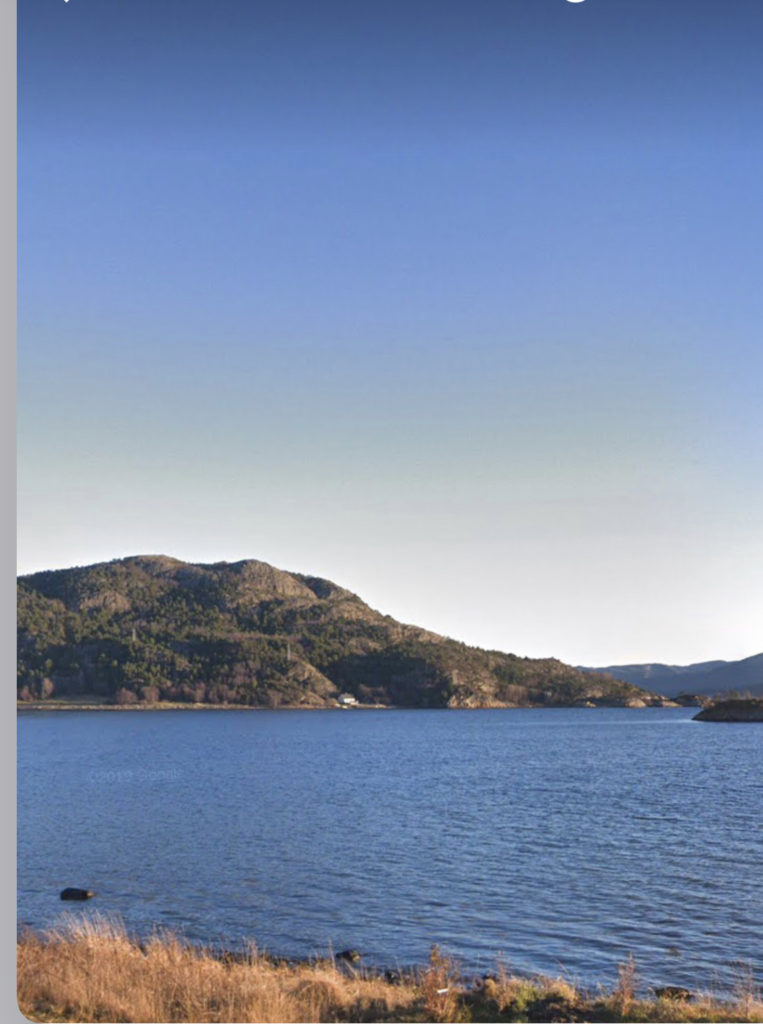

Stjørnfjorden er en prima fiskefjord. Men Eidsbukta er en værhard plass. Strøm og vind arbeider med sandbotnen og flytter på bankene fra den ene måneden til den neste. I gamle dager hadde bygdas folk båtbruk ute på holmene, der det var litt mindre grunt, sjøl om det stod tett i tett med naust på land, rundt munningen av Eidselva, og ellers dro de båtene på land i Båtvika (ikke så langt fra Trillsteinvika). Sørvesten står rett på inn fra havet, og det er mye av den. Og den kommer fort.

Men så, når det «skin tå», finnes det ikke finere plass.

Så, i 1961 står det en flott molo ferdig i Høybakken. Båthavn, smul som en søledam, der båtene ligger trygt. Tenk å ha båten sin der! Slippe å passe den dag og døgn, for at ikke sjøen og plutselig uvær skal slå den i stykker. Anna og Edvin blir enige om å «sule opp» i Eidsbukta og heller bygge seg hus i Høybakken, rett over den nye båthavna.

Men hva skal de gjøre med Strandstua? I mellomtida har søster av Edvin, Kitty, blitt husfrue på Eid, og i 1963 bestemmer Edvin og Anna seg for at de vil selge «Strandheim» tilbake til gården, og så «kan det liksom være Kitty sin sommerstue».

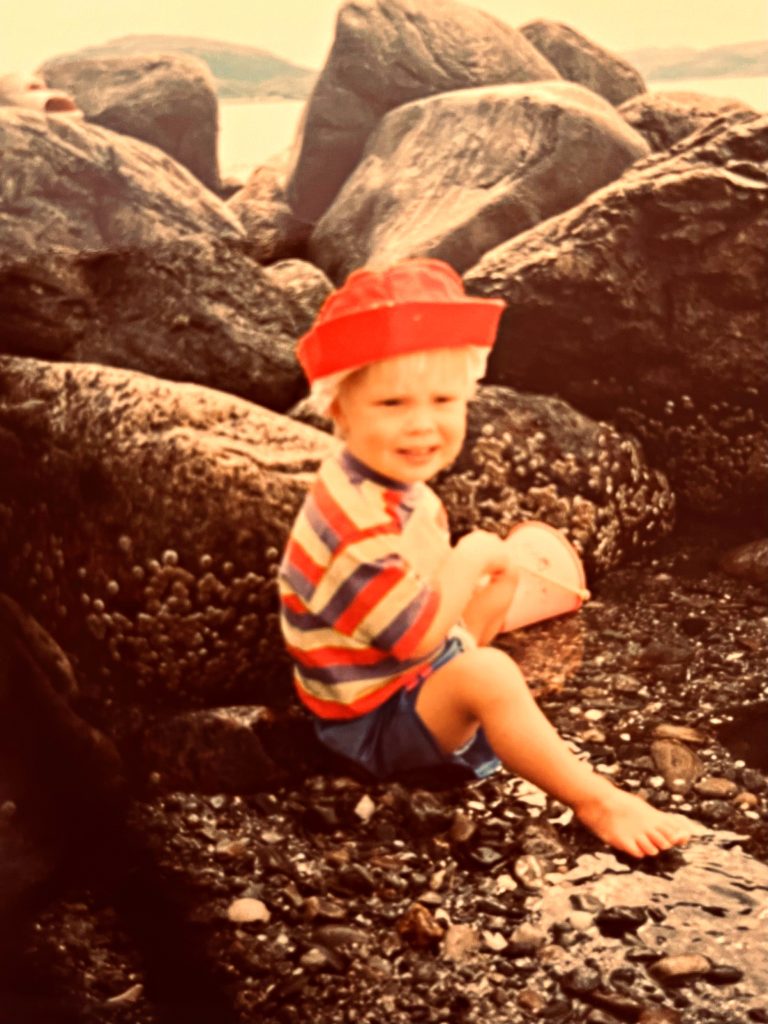

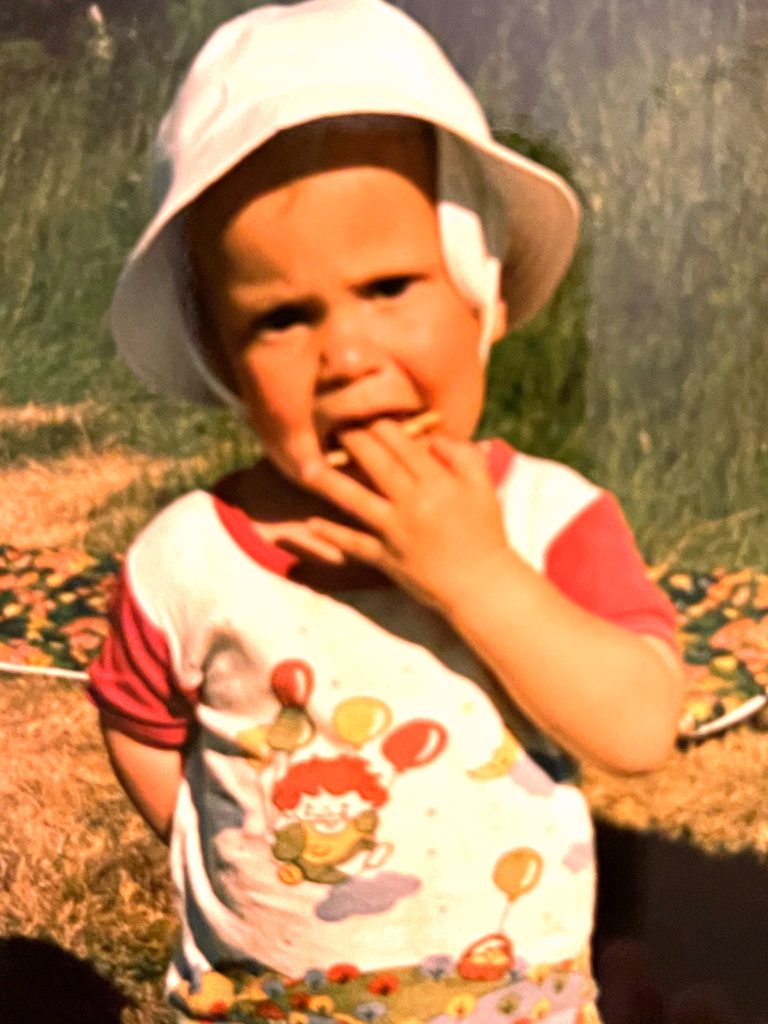

Og det blir det. Kitty er blitt tobarnsmor, Hans kom i 1961 og Gunnar i 1962, og straks det er finvær, inviterer Kitty slekt og venner til Strandstua, til soling og piknik og sosialt samvær. Det skal bemerkes at Kitty (svigermor) sannsynligvis er blant de mest sosiale vesener som noen gang har betrådt jordkloden. Så det skjer aldri at hun og barna er der alene, det er alltid flere i laget. Når værgudene er på lag, starter Kitty fra morgenen av; skreller poteter og steiker skuffkake og legger i korga, henger korga på sykkelstyret, og belager seg på lange dager på plena på Strandstua. Karene driver onn oppe på gården, og får beskjed om å stille opp på Strandstua om de vil ha middag. Med påfølgende middagskvil i solsteiken.

Mens hun venter på at storinnrykket av dagens gjester skal innfinne seg, plukker Kitty stein i fjæra. En halv meter bred stripe i støa renskes for stein, slik at små føtter skal ha det bedre når de tripper ned til vatnet. Dette er et Sisyfos-arbeid. Neste finværsdag må en starte nesten på nytt igjen. Men da er det jo bare å starte på nytt igjen, da. Folk må jo få slippe å gå med sko når de skal ned og bade!

Det er utrolig mange som har fantastiske minner fra denne plassen. Unger og voksne kravler over hverandre, det er luftmadrasser og baderinger å plaske rundt i for de minste ungene, gummibåt og plastbåt for de som er litt større.

Barnevogna kan en plassere i skyggen bak Strandstua, eller legge solsøvnige unger til formiddagsdupp i køyesengene på soverommet. Det er do, riktignok bare en utedo, men det går. En kan skifte til badetøy inne i huset. Det er gassbluss på kjøkkenbenken, så en kan varme barnemat til babyen. Og om en gruer for at det blir litt sein middag når en kommer heim etter en lang dag i sola, var det rart om ikke Kitty hadde et par karbonader og noen nypoteter på luringa. Og så vanker det alltid skuffkake, i alle varianter, til kaffen. Om en ikke vil forsmå.

Og det vil en jo ikke.

Dette bildet er av alle barnebarna til Kitty på Strandstua (Bibbi har tatt bildet).

Det blir et stort hull etter slike folk når de dør. Og når Kitty dør i november 2002, blir det et hull som er ganske mye større enn hennes beskjedne høyde skulle tilsi.

Det går liksom ikke an å være på Strandstua nå. Det blir så rart. Dette er jo Kittys sommerhus. Det går ikke an å være her når ikke hun er her sjøl. Vi skyr Strandstua, faktisk i flere år.

Men da er det andre som syns det er desto kjekkere å være her, når de plagsomme eierne ikke er her. Stadig må vi plukke søppel etter folk som villcamper på plena, folk som rigger seg til på hagemøblene, og går i fra rykende engangsgriller i det tørre graset på plena.

En dag har tydeligvis noen like godt satt seg til oppe på terrassen og grilla med engangsgrill. De går bare i fra den på hagebordet når de er ferdige, og neste gang vi kommer innom for å sjekke at alt er bra med Strandstua, finner vi engansgrillen hvelva på dørstokken. Vinden har tatt engangsgrillen og blåst den inn til veggen, opp-ned mot ytterdøra og dørstokken. Kullet har svidd merker i dørstokken og trappetrinnet før det har slokka av seg selv. Men her er det åpenbart at det har vært branntilløp.

Dette går jo ikke. Vi blir nødt til å ta tak i dette, før Kittys sommerhus er en saga blott.

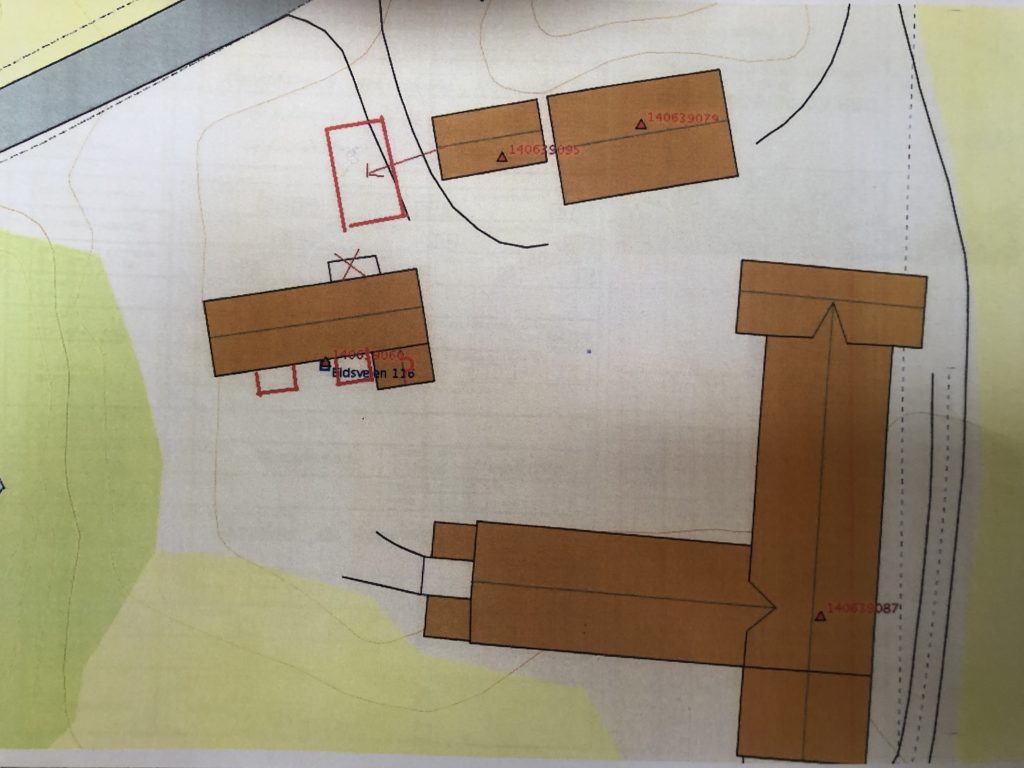

Vi bestemmer oss for å renovere. Så kanskje det blir LITT mindre Kittys sommerhus og litt mer vårt eget. Vi søker kommunen og fylket om å få restaurere Strandstua, og få bygge på litt i retning nord og øst. Det blir innvilget.

Så begynner vi å rive. Men tømmeret er pill råttent etter 70 år i saltvannsrokk og sørvest. Vi plukker ned svampete tømmerstokker med bare fingrene. Dette kan ikke brukes.

Vi må søke på nytt, nå om å få sette opp et nybygg. Det er et lengre lerret å bleke, viser det seg. Det er strengt å få bygge i standsonen. Uansett. Men etter noen runder med søknader, anker og nye søknader, og direkte kommunikasjon med fylkesmannens kontor, går søknaden igjennom. Det viser seg å være veldig viktig at vi ikke har revet den gamle hytta før vi søker.

Så lenge bygget som står der, er lovlig oppsatt, får vi lov å sette opp et nytt bygg, litt mer etter dagens standard. Og Edvinsstua er lovlig oppsatt — den ble satt opp flere tiår før plan-og bygningsloven ble vedtatt. Vi kan begynne å rive.

På taket er det lagt bølgeblikkplater oppå det gamle taket av «handklåvvespon». Dette spontaket har altså ligget og tørka seg i femti år. Hans river av bølgeblikkplatene for hånd og løfter så halvparten av takflata i ett stykke, med gravemaskinen, bort på bålet nede i fjæra. Bålet er langt nedenfor flomålet, så vi tar ingen sjanser.

Men idet flammene får tak i den knusktørre taksponen, skyter det ei søyle av røyk og flammer opp gjennom taket, synlig i kilometers omkrets. Dette er den store skogbrannvinteren, der hele Trøndelag herjes av lyngbranner og skogbranner. Bålforbudet er oppheva i Bjugn og Ørland, men ikke i Fevåg og Rissa, på andre sida av fjorden.

Odelsgutten er plutselig på tråden. «Hva er det dere holder på med der nede? TO uniformerte politibiler er på vei ned til Strandstua!» UPS… Men vi HAR kontroll, altså. og det er ikke ulovlig å brenne bål her i Bjugn.

Den ene politimannen er en slektning av Edvins kone Anna, og han er vel offisielt den første som lurer på om vi kan tenke oss å selge denne tomta. Dessverre, det kan vi ikke tenke oss. Men det har ikke akkurat mangla på tilbud. Jeg mener det har vært 28 forespørsler så langt.

Det er veldig effektivt å rive med gravemaskin. Men det er et pokker til arbeid å rydde det opp igjen. Hundrevis av trillebårlass seinere, der vi har raka og plukka og sortert murstein, trebrokker, og bygningsskrot for hånd, kan vi sette opp ny grunnmur.

Vi er så fantastisk heldige å få hyra inn en legendarisk dyktig snekker. Han kan sine ting, og i løpet av tre uker står råbygget ferdig, og bygget er tett. Alt det innvendige arbeidet gjør vi sjøl. Og terrassen. Men med masse gode råd fra snekkeren.

Vi bygger terrassen først. Den er viktigst. Og sommeren slår til med helt fantastisk vær. Inne har vi strøm på kjøleskapet og kaffemaskinen. Ellers trrenger vi bare terrassen, så lenge.

Det er fruen i huset som står for all glava som skal pakkes. Husbonden får influensasymptomer hver gang han er i nærkontakt med glava. Og så er vi så heldige at vi kjenner en fantastisk dyktig elektiker.

Men det er uansett ikke noe mangel på annet å gjøre. All fritida vi har, kvelder, helger, ferier, i to år. Her ligger det utrolig mange hundretusen i egeninnsats.

2015 står hovedetasjen ferdig, til feiring av fruens femitårsdag. Vi dekker til 54 personer på terrassen. Så det er en solid terrasse. Det er umota å gå løs på andre etasje. Hele høsten går uten at vi kommer i gang. Men så, på etterjulsvinteren, tar vi oss på tak igjen.

Hver kveld det samme: «I dag tar vi fri fra husbygging, sant?» «Ja, vi fortjener litt fri nå.» «Det er klart, vi kunne jo ta ei lita time, bare. Bli ferdige med akkurat den veggen, så blir det bedre inneklima der.» «Ja, det kunne vi. Vi tar ei lita time, da.»

Og så ble det å holde på til midnatt i dag igjen…

Men i 2016 er vi ferdige. Og jammen er det verdt alt arbeidet.

I byggesøknaden fikk vi også innvilget å sette opp et lite naust. Og like før holdbarhetsdatoen går ut på den tillatelsen (å jo, det er faktisk holdbarhetsdato på slike), får vi satt opp naustet også.

Vi har hatt utallige fantastiske stunder på Strandstua. Med familie, venner, folk vi er glad i. Vi håper og tror at det blir mange flere, når livet blir litt mer normalt igjen.

Det aller flotteste med Strandstua er den fantastiske utsikten. Den går det ikke an å bli lei av. «Verdens finaste plass,» sier far til Malene hver gang han er på besøk. Vi er vel ikke akkurat uenige med ham i det.