I work with language, and within the theories that I use as my framework, the goal is to find out what is common and universal to all languages in the world. We are sort of looking for the atoms of language, and we want to describe these atoms. In a way we are trying to arrive at a periodic table for languages.

An element of this sort, a feature that all languages need, we call "predication". It might sound complicated, but in essence we can think of this element a a kind of hinge. If I say, for instance

THE FISH

I have not, thereby, given you any information about anything in the world. Nor if I say

IS ALIVE!

But using this fine hinge that all languages posess, and link these two together, I get

THE FISH IS ALIVE!

Now I have given you a piece of information about something that you might not know, and then you may act upon this new knowledge. Without this hinge we could not use language to transfer information, and thus this hinge is a basic element, an atom, in natural human language.

To find these basic elements it is not enough to know and study Norwegian. I have to compare all the languages I know, and some that I do not know, to discover how these basic elements behave. And I need to coopoerate with researchers who are experts on languages that I don't know, so we may compare these basic elements across languages.

This means that even though I live on a farm far in the countryside in provincial Norway, I still get to meet the entire world through my work. The world comes to us, especially to my university in Trondheim (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU), but it also happens sometimes that good colleagues become good friends and visit me at our farm.

Leonie is one of these. Leonie is a Dutch linguist who I have known for a number of years, and even long before that, I used to read what she wrote about her research. Because this is one very smart and interesting lady.

Leonie is extremely fond of animals. At home she has a big dog (Roos) and she takes every opportunity to visit farms and domesticated animals in the Netherlands. So you might imagine what was on her mind already at her first day of visiting me at Eide farm.

"Can we go and meet the cows?" Leonie asks. "MEET the cows?!" I reply. "They are inside for the winter, Jon Gunnar has taken them all inside the barn." "Yes, but can we go into the barn and meet them?" Leonie asks. I give a long sigh. I just washed my hair! There is no way you can spend time in a cow barn with live cows in it and not have the smell getting stuck in your hair and your clothes. "Does it have to be right now? Can't it wait until the morning? I just washed my hair!" I object.

"But I don't mind going there by myself," Leonie says. "I don't mind, and I am not scared." Well, it is not that I am scared either -- except for the prospect of cow smell in my newly washed hair. And it is not like the cows will harm her in any way. Demonstrating my total lack of the skills becoming of a good hostess, I leave it to Leonie to visit the barn by herself.

Later Leonie describes her visit to the cow stall in an almost poetic way. It is quite dark, the cows are very close to each other, and close to the entrance. The cows are facing each other in two rows, and Leonie feels a bit like an intruder. The cows are calm, quiet, and close. As she enters, the cows turn their heads in her direction and try to establish eye contact. They have clearly noticed her arrival.

The cows look at her with their big brown eyes, and one of them (she cannot tell which one) makes a deep sound: "mmmmmmm". The farmer is not there, and Leonie decides to come back a bit later. The next time she enters, one of the cows makes exactly the same sound as before. The cows only make this sound when she enters the barn, not later, even if she stays in the barn for a while.

(This is a later recording, the cow Beatrice is making the sound, and Jon Gunnar made the recording).

Leonie is pondering. Could it be that she has just had the experience of being greeted by a cow?

But cows don't greet humans, do they? Only humans greet each other with these special rituals. Also, Leonie has been studying Dutch cows and how they interact with their owners. And she is pretty certain that she has never heard a similar sound from the Dutch cows. The Dutch farms are obviously usually much bigger than the farm at Eide, with a lot more cows and typically a much more peripheral relation between the cows and their caretakers. But still.

This needs a more thorough investigation. "Kristin," Leonie asks me the same night. "If a cow makes this long, deep mmmm-sound when you enter the barn, do you attach any particular meaning to that sound?"

"I guess," I respond. "To me it means 'come here and let me look at you a bit closer, there you are, here I am.'" But it is also a message to the rest of the cows, that the event of me entering is not scary, nothing to be alarmed about." Leonie obviously finds this interpretation very interesting. For some reason. I would think this would be obvious to anyone raised on a farm.

The next day we are back in my office at the university. "Too bad," Leonie says, "that there is nobody but you in this department who knows anything about cows. Then we could have checked if anyone else had the same inerpretation as you." I burst out in laughter. "Half of the people working with Scandinavian langauges in this department are farmers", I am giggling. "I hardly think it will be a problem to acquire another informant."

We call on Professor Stian, who was raised on a dairy farm, just like me. Stian gets the same question, out of the blue. It is quite obvious that Professor Stian is a bit puzzled by the question, and he allows himself a characteristic little puff of laughter. "Uhhhhh, well..." he roames around in his mind. "To me that sound means that the cow has seen you, "you are there, I am here, kind of." The cow is not afraid or anything like that, it is a sort of emphatic sound, friendly and curious."

My jaw drops. It sounds as if Stian and I have agreed on this interpretation on beforehand, since this rendering is in part word for word the same. But we have not agreed on anything, we have not discussed it. And yet we agree completely on what this sound means. So when the cows we know are greeting us, we both know that this is exactly what they do. Without giving it much thought.

But Leonie has given it a great deal of thought. She starts comparing the communication she observes between cows and their caretakers on small farms like the Eide farm, and that taking place on huge, more factory-like farms, typical for the Netherlands and other European countries. A bit later in the fall she visits such a big farm, with more than 150 dairy cows. She asks the farmer on that farm what his interpretation is of this mmmmmm-sound. "I have never heard such a sound," he says.

Still, the picture is a bit more complicated than merely the size of the farm. Leonie finds that most calves try to greet their caretakers this way. In the Netherlands it is not uncommon that cow stalls have one or more open walls. Norwegian cow barns, like the one at Eide, have four closed walls, because of the climate. When cows are enclosed (that is, not outside, or in a barn with open walls), they make this sound much more, preferably to people they know, and sometimes they will give this sound even upon hearing the sound of the tractor, if the driver is someone they like and trust.

If you pay attention you can easily find other Norwegian farmers who claim to understand what cows express with different types of sounds, not just greetings. Like Svein Arild Averøy, who says that "There is a moo for anything. I can tell whether the sound signifies that one of the cows is in heat, if there si a calf being born, if there is a water leakage or whether one of the cows is lose and the others are telling on her."

Why is it so important to establish that cows greet people? A greeting is usually an expression of respect. When cows show us respect, and greet us, it becomes more obvious that they themselves deserve our respect. Unfortunately, not all cows receive this respect today. This is one reason, among many, why this reserch is important.

The reserach on the communication between animals and humans is a field of research which is only in its beginning, but it is a field which will become increasingly more important in the future. The new generation of young people, which means eventually also researchers of this generation, are very much committed to animal rights and how we respect them.

Greta Thunberg wants to save the planet, and is also committed to animal rights.

Therefore I am a bit proud that one important step in this research was taken on this farm, on Eide, not very long ago. With our cows, on our farm.

Of course, one might object that it is not very strange that Norwegians communicate with their cows. They are fellow inhabitants of the farm, the dairy cows in the barn have all been born here, and had their early years in the pen outside with the other calves. We have known every cow for a long time.

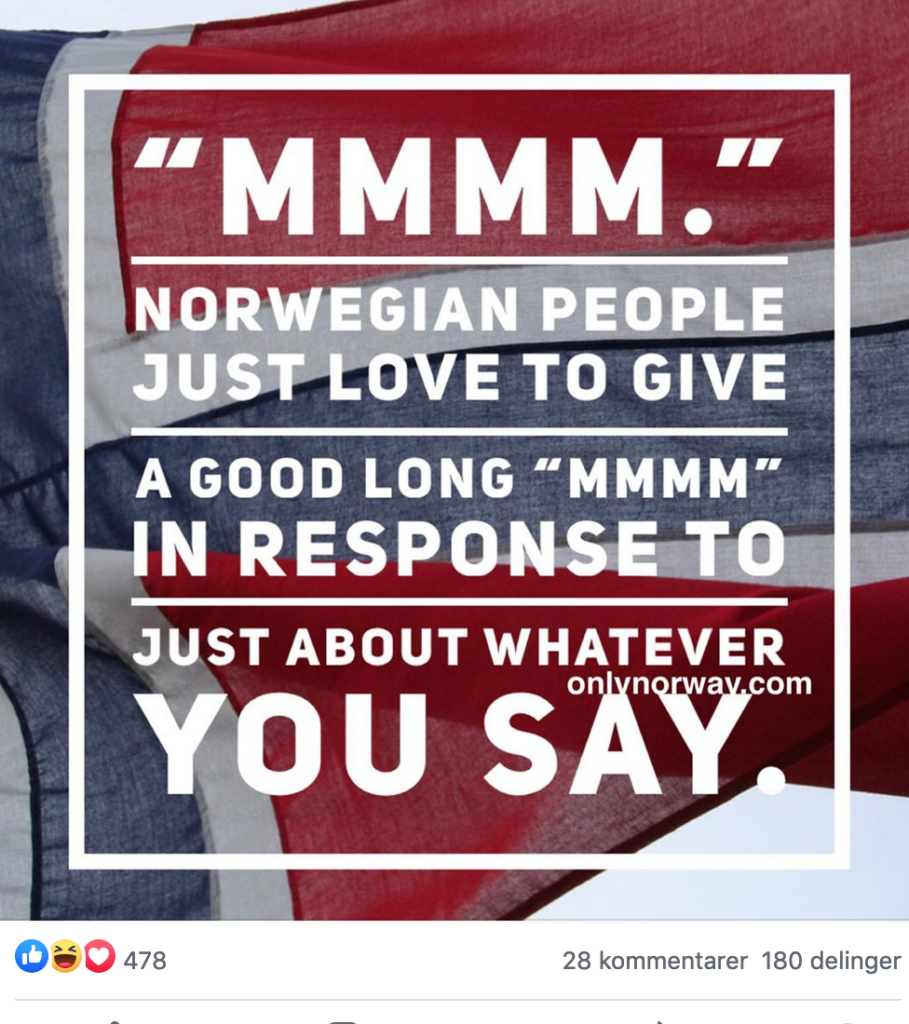

People used to say that in Lierne people treated shep mostly like other people, which is why the sheep talked the local dialect until the sixties. But I wonder if we might also look into the following claim from our American friends here, about a fact that possibly could ease the communication between people and cows regarding the mmmm-sound explicitly.

I want to emphasize that this was a joke.

Also, the mmm-sound that cows make is very different from the one Norwegians make. Just listen:

Still --- it is a fun observation to make.